By: Kevin Gordon

I’m assuming that most all of the three letter architectural firms, TVS, SOM, HKS, etc. require each employee to submit to, and submit, an annual performance review—the APR. Ours was temporarily titled the “360 Review,” until it was pointed out to HR that employees would be reviewing themselves. I’m proud to record that I routinely score high marks in design and revenue production. However, peer group comments over the years have a consistent theme—I’m irascible, difficult, quick-to-judge, dismissive of others, etc. All the common pathologies of intellectual vanity.

Not a people person.

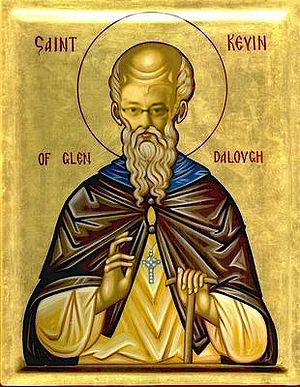

In my defense, I’ll submit to the HR bench that my little mother named me after one of the saints, Saint Kevin, whose given name Coemgen (anglicized Kevin) means “fair-begotten,” or “of noble birth”—a recipe for future vanity. Kevin was the patron saint of hermits, but in his neighborhood revered for kindness to animals. He (I) lived in happy solitude in a bronze-age tomb near Dublin for most of his 120 years in order to avoid the company of his (my) followers.

Not a people person.

So, grace to the family tree, I can’t help that I’m really fond of dogs, with a near spiritual weakness for the beauty of a Basset Hound’s ears. I have a 40 year old bar coaster from France on the kitchen table that philosophizes, in the best tradition of French philosophy “plus que je vois les hommes, plus que j’aime les chienes,”—snorting against that adoptive family tree of basset favoritism was a heretical English bulldog named Winston. He was a person in a dog suit, although I didn’t hold that against him. The next time I get to chat with The Boss, I need to complain about His seven-day creation oversight in their longevity—they’re not meant to last.

Let me tell you, sainthood does have its perks. It gets you an invite to the annual family picnic with The Boss, and a halo… But what really has peeved me over the years was the occasional responsibility to put on some pants, come out of the cave and opine on matters of morals and ethics with people who kept ringing the doorbell in search of guidance into the human condition.

Such as doorbell-ringing Architects, who often don halos, view themselves as spiritual compass needles, and are fond of invoking a moral/ethical argument as a means of boosting the ad campaign for their respective brands of style. Marcel Breuer, for whom “the definitive expression of a purpose of a building and the sincere expression of its structure…one can regard this sincerity as a moral duty.” Or Gropius “the ethical necessity of the New Architecture can no longer be called into doubt.” Alternatively, Sir James Stirling on his student tenure at the Liverpool School of Architecture—“I was left with a deep conviction of the moral rightness of the new architecture.”

I need to cut the landline and get on a do-not-call register.

They remind me of the defunct cigarette brands that were my favorites “True,” “Merit,” and most ironically “BelAir” that shamelessly stood out as hitching your wagon to a higher marketing horse.

Confessionally, most of us Saints aren’t smokers, although I bet a lot of us stopped at the roadside convenience store on the way to the family picnic. As my fellow saints bellied up to the plexiglass-shrouded checkout counter with their butts of choice they were smoking a trinity of truth, virtue and beauty, or at least pleasure.

Like their mid-century modern icons, The AIA, the American Institute of Architects, also seeks moral/ethical validation with its “Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct.”As background, there’s little difference between ethics and morality—one’s a Greek word and the other Roman, for a broader concept about doing the right, honorable thing in this life. Ecclesiastically outlined in six Canons (with Roman numerals!!!) the AIA Code of ethics is largely a Boy Scout manual of professional conduct—“Members should serve their clients in a timely and professional manner” or “ Members should pursue their professional activities with honesty and fairness.” Two, however, stand out as more transcendental emissaries of morality—Canon I, E.S. 12 and the entirety of Canon VI.

The former, under Canon 1, General Obligations, requires that “Members should continuously seek to raise the standards of aesthetic excellence, architectural education, research, training and practice. It always seems subversively apologetic that the essential mission of design- to make beauty, is allowed two whole words.

The latter Canon VI, Obligations to the Environment, states, “Members should recognize and acknowledge the professional responsibilities they have to promote sustainable design and development in the natural and built environments and to implement energy and resource conscious design.”

Although progressively devoting an entire Canon to the environment, the AIA stands on the shore suspicious of the thin ice of a potentially client alienating policy. They shy away from mandating that all members support the AIA 2030 Challenge, which would push the profession into the moral imperative of a Paris Accords regimen of ecologically responsible design.

For the lay reader, the 2030 challenge was scripted by Ed Mazria, a visionary Brooklyn/ New Mexico architect (once recruited by the Knicks to play hoops) as an anti-global warming template in recognition of our profession’s contribution to the retreating glaciers in Switzerland. He should be given the Congressional Medal of Honor.” At a minimum, Pope Francis should canonize him into sainthood.

Saint Ed.

Of all the saints at the annual family picnic with The Boss, Tom is my favorite. The younger crowd at the “children’s table” respectfully demure to him as Saint Thomas of Aquinas. My good friend Tom was one of the most prolific writers of our medieval peers, over eight million words—tenfold the extant writings of Aristotle. That’s a tribute to what the human intellect can accomplish without the distraction of the internet.

Saint Thomas also skated out onto the thin ice that the AIA admires on another shore but will not dare to venture upon—the moral mandate of making beauty.

Saint Thomas, advancing a near heretical Greek Aristotelian thesis, believed that the making of beauty—objectively framed by proportion, integrity and splendor was equally mirrored by the near sinful subjective perceptions of joy or pleasure. In his Summa Theologica, my good friend Tom said, “We call those things beautiful which please when seen.” In the more than 750 years since he wrote that poetic merger of intellect and soul, my chest still tightens with every reading. What followed was an early renaissance logic tree leading to pleasure = good and good = virtue. When we are attracted to beauty, we are attracted to goodness, and that desire, that pleasure, underlie all the four cardinal virtues, or moral virtues, of the classical world.

It’s seems a sin to reduce his Summa Theologica to a paragraph, but such is the nature of the devil’s tool—the internet. Sorry Tom.

The Boss’s religion seems always to have one foot on the dock and one in St. Peter’s boat. It is rooted, in the moment, in penitence against the past and optimism for the future. In my cave, I think often of the push and pull of beauty. And, in the languor of my gaze beyond all the sleeping sunlit bassets, I hope that beauty endures.